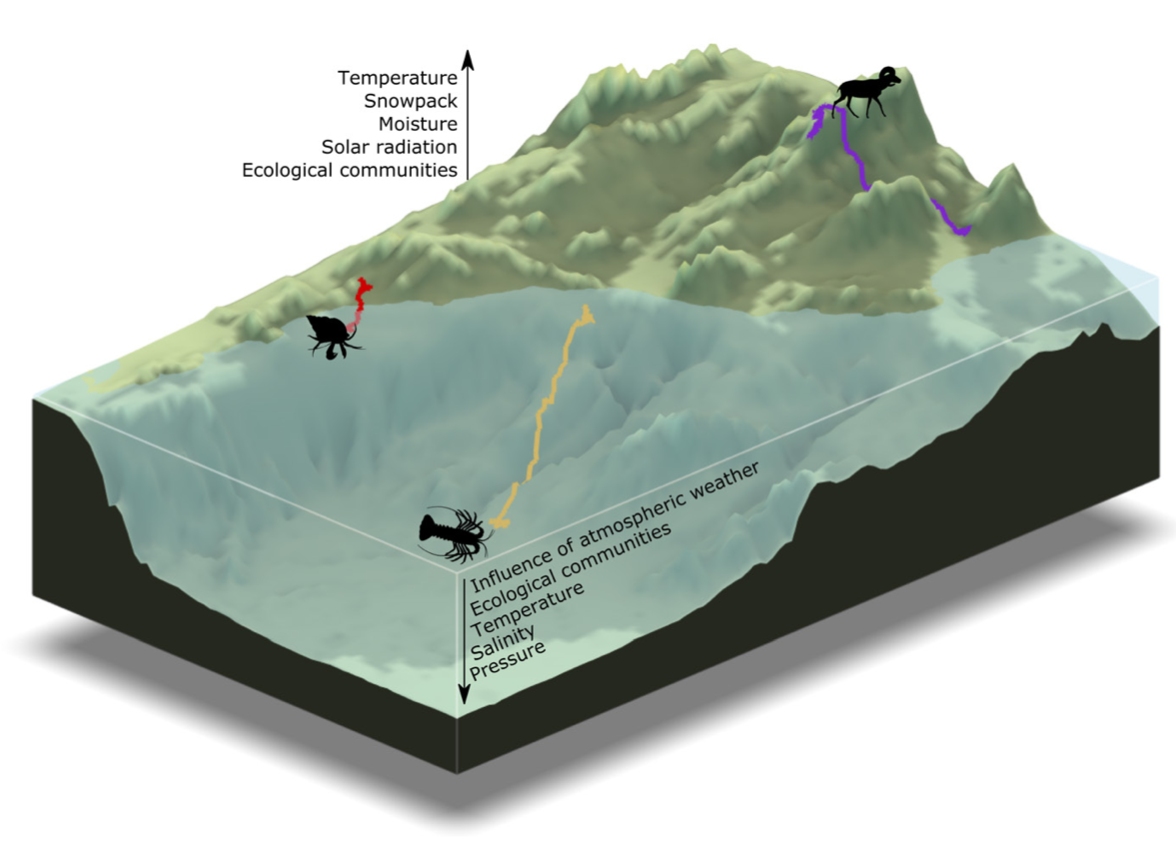

Animals famously migrate across great distances to forage, avoid stressors, and reproduce. But, they can also move vertically - across elevation in mountains or bathymetry in marine environments - to accomplish similar goals. By moving vertically through “landscapes of relief”, vertical migrants can achieve change in many aspects of their local environment, from ambient pressure and temperature, to sun exposure, and predominant plant communities (John and Post 2022 Ecography).

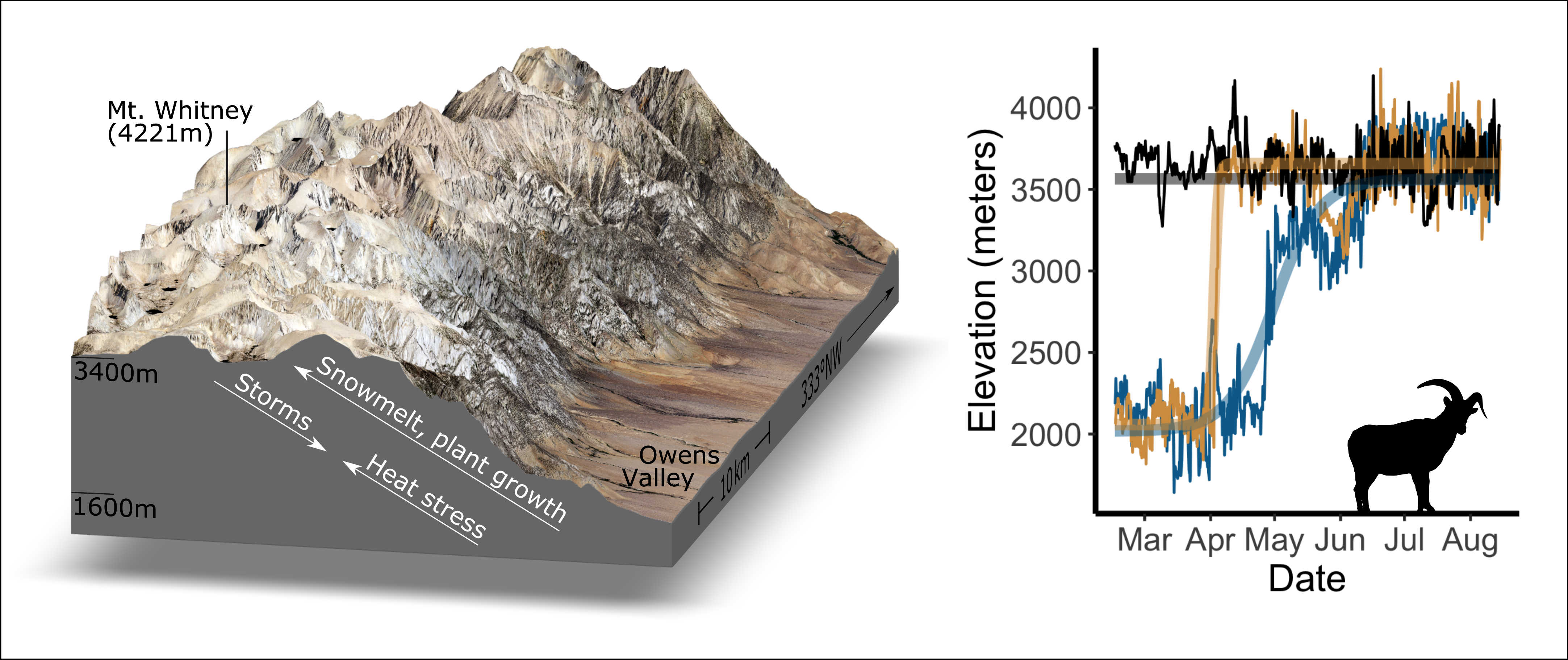

Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep are one such vertical migrant (John et al 2024 Scientific Reports): these endangered alpine specialists migrate from the Owens Valley to the High Sierra each spring when snow melts, wildflowers flourish, and bighorn give birth to their young. Their uphill spring migration helps them maximize access to food while avoiding hungry mountain lions that live at lower elevations. But, different individuals use different migratory strategies: Some stay at high elevations year-round, while others are migratory. Even among the migrants, some move from low- to high elevations quickly while others migrate more slowly. Slow migrants may undertake many up-and-down movements throughout their migratory season.

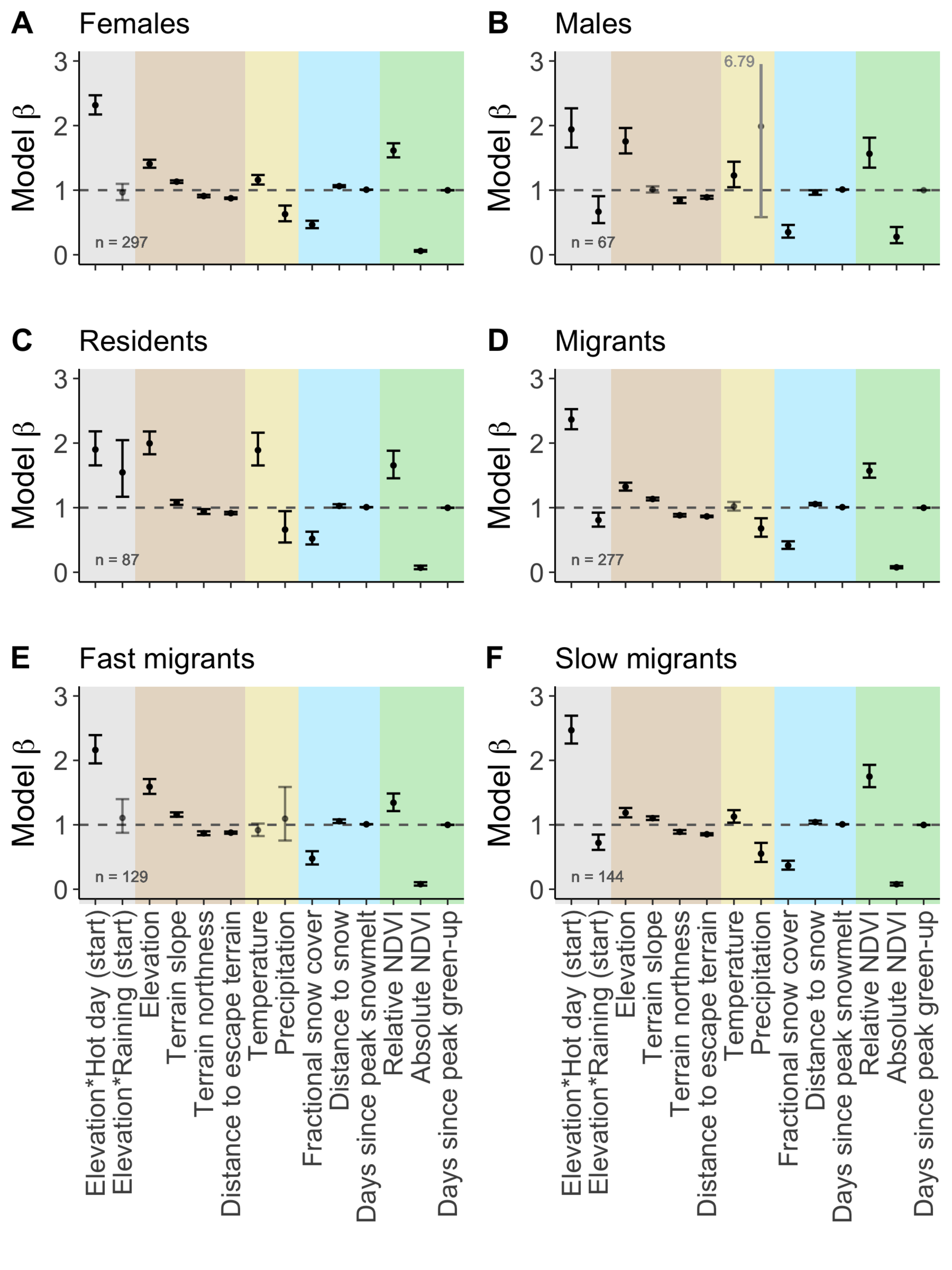

In this project we set out to understand the drivers of up- and down-slope movements by Sierra bighorn during their spring migratory season. We expected that heat stress (the Owens Valley can get very hot!) would drive animals uphill, where temperatures are lower, but that storms (which can be dangerous on exposed alpine slopes) would drive animals downhill. We used a GPS collar dataset from >300 animals over the course of 20 years, along with a series of environmental layers to summarize daily heat stress, precipitation, snow cover, and foraging opportunities, in a step selection modeling framework to see how resources and stressors might impact bighorn movement dynamics.

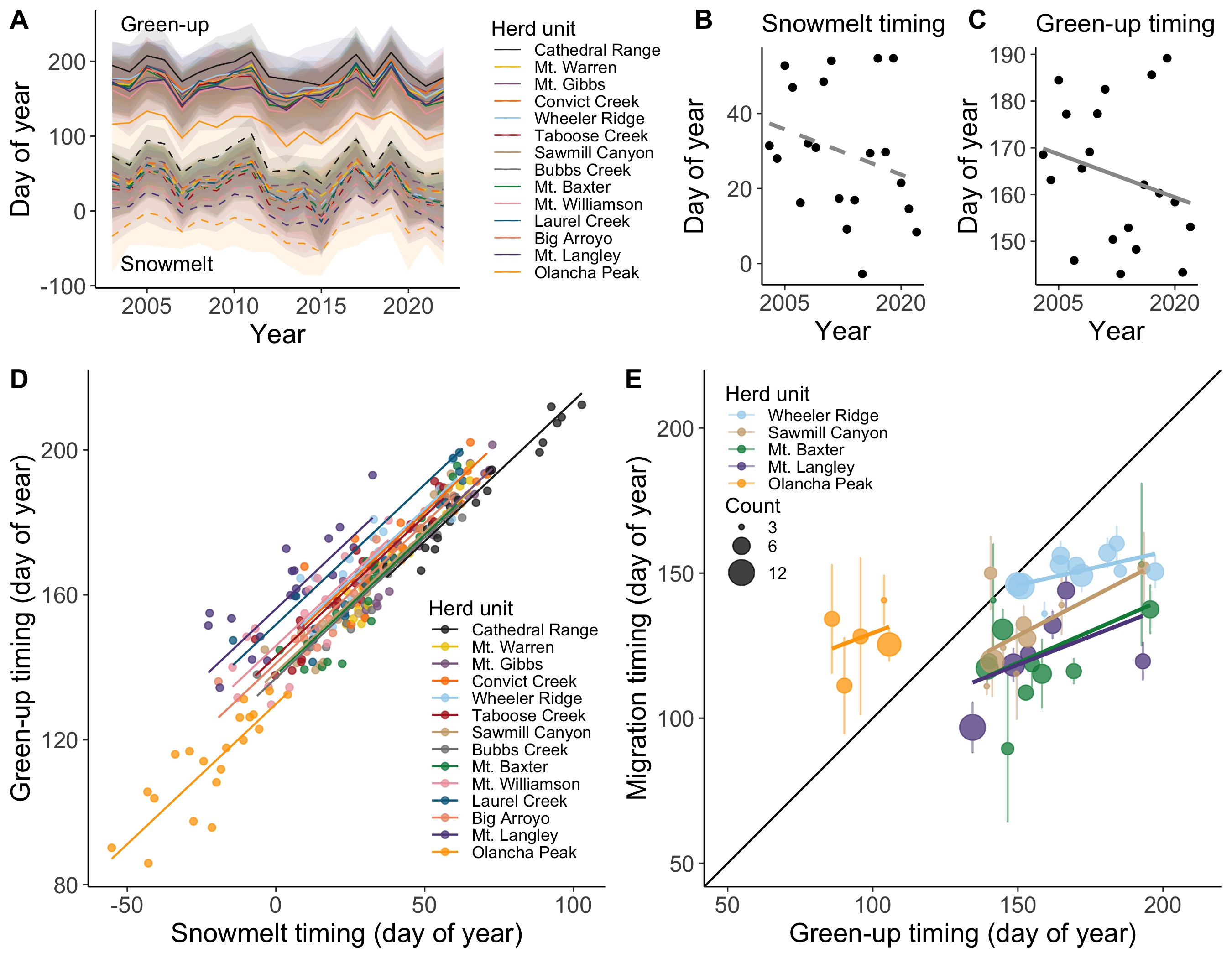

Snowmelt and plant growth were highly dynamic over the two decades we investigated (2003-2022). Snowmelt timing varied by up to two months over the course of the study. Snowmelt timing and plant green-up timing both advanced (i.e. became earlier) throughout the study. Areas with earlier snowmelt had earlier plant growth, and bighorn that lived in areas with earlier plant growth also tended to migrate uphill earlier in the spring.

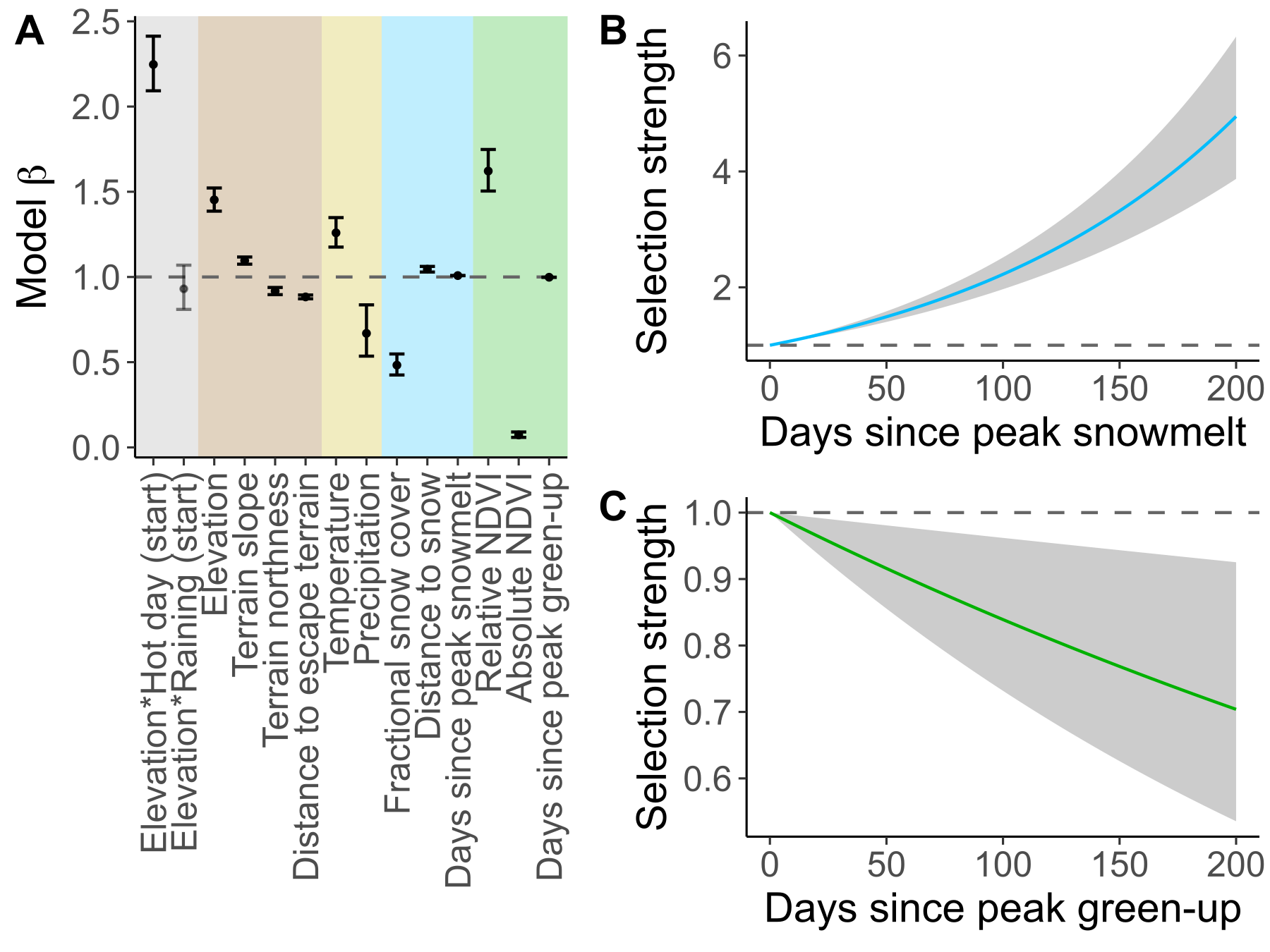

Bighorn tracked snowmelt and green-up throughout their migratory season, although they always stayed close to escape terrain - steep areas where they could escape from a predator if one happened to come by. And although they sought out areas that had low overall biomass (i.e. selected against “absolute NDVI”), they moved toward destinations that had high “relative NDVI” (that is, sites that were near their peak level of plant productivity for the year). Whereas high temperatures drove uphill movements, indicated by the significantly positive interactive effect between high temperatures at the start of movement and destination elevation, our dataset indicated that storms drove downhill movements for only some bighorn: those with slower, more flexible migratory strategies; and rams, which enjoy a freedom from responsibility of rearing lambs.